How’s your day?

If this were the first day of a design sprint, you’d be all pumped up about the highly stimulating, brains-expanding, and business-propelling four-day workshop you are starting now.

We have seen what is a design sprint, what it’s about, and what it can do.

Drink your coffee, and let’s see how each day is structured to get your team moving forward, fast.

In this series of posts, we’ll look at each part of a design sprint workshop, the Pentalog Growth Factory way.

First, the rules

You knew there were some, didn’t you?

Here they are:

- There will be no devices during the workshop exercises (unless otherwise warranted).

- There will be short breaks roughly every 60 minutes.

- Lunch will be at around 12:30, and it will be light, so everyone can still focus in the afternoon.

- The participants are going to work “together alone.”

- Discussions will focus on something tangible, something that you can show.

- Getting started is more important than being right.

- There will be no sprint if the decider is not in the room.

A reminder: there’s no need for creativity to get through the sprint. The process generates the creativity needed to solve your challenges.

The goal of the 4-day workshop is to decide what challenge to tackle and to have figured out and tested one or more solutions to that challenge.

Bringing the team together

A design sprint workshop at Pentalog starts with the usual presentations of the participants, of course. It’s easier to sprint if you feel part of a team!

Then, to make sure everyone is on the same page, we review the process and the rules, and what to expect.

As we discussed in a previous post, the participants should come from different departments or functions. Pentalog will provide the Sprint Master and one or two people to join the client’s group.

The Decider will have been chosen before the start of the meeting.

Expert interviews

The work starts now with expert interviews, all together at once, recommends A.J. Smart, an agency that has developed an approach similar to Pentalog’s.

Who are these experts? They might be brought from the outside of the design sprint team or be part of it.

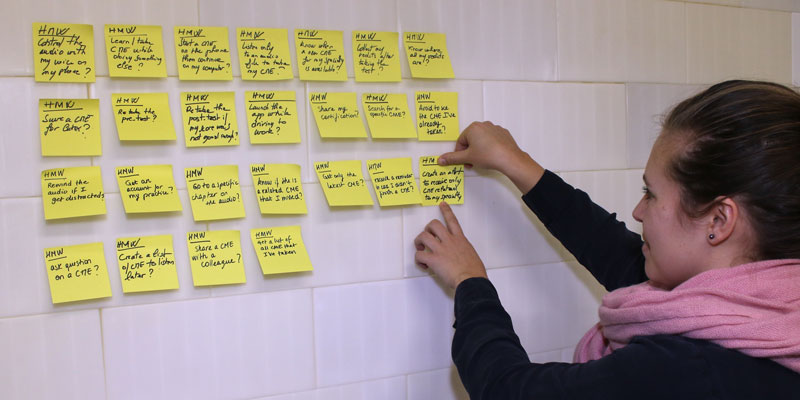

While the experts answer questions from the group, participants will take notes on post-it notes in the form of “How Might We” statements.

“How Might We” statements

HMW statements allow rephrasing a problem, in a process developed years ago, as explains Jake Knapp in his book Sprint:

“It was developed at Procter & Gamble in the 1970s, but we learned about it from the design agency IDEO. It works this way: Each person writes his or her own notes, one at a time, on sticky notes. At the end of the day, you’ll merge the whole group’s notes, organize them, and choose a handful of the most interesting ones. These standout notes will help you make a decision about which part of the map to target, and […] they’ll give you ideas for your sketches.”

This method calls for participants to write down ideas in a How Might We format. For example: “HMW make our customers feel we sell the best product?” or “HMW communicate our values on the Web?”

Naming the problem

Each participant must come up with his or her HMW statements. Let’s not forget that most of the work in a design sprint workshop is done together alone. That means that everyone should devise their solutions without sharing it at first.

How many HMW statements should each participant write up?

About 10, says Jeff Mignon, Pentalog’s Chief of Growth: “The goal at the beginning is to push people to name the problem, and there’s no limit to the questions people can ask.”

What happens to the “How Might We” notes?

You’ve got all these sweet little yellow sticky pieces of paper. What do you with them?

Just stick all of them on a wall, without any organization at first.

The next step will be to classify them by themes. What themes? You’ll figure it out by reading the notes. Themes should emerge naturally.

Just identify the themes using new post-its on top of each column on the wall.

Don’t spend too much time on this. Ten minutes is enough, recommends Jake Knapp.

How does that look?

And the HMW Oscar goes to…

Ok, there’s no such thing as an Oscar ceremony for the HMW statements. But you’ll need to vote to pick the issues to prioritize.

The vote uses dots to pick the winners. Each participant gets two large dots. The Decider gets four because… she or he is the Decider.

The most-dotted notes will be transferred to a different wall for the next step.

Remember: the Decider has the last word. The participants’ dots are opinions expressed to the decider.

Picking a long-term goal

The next task participants must clear is defining a long-term goal:

“Your goal should reflect your team’s principles and aspirations. Don’t worry about overreaching. The sprint process will help you find a good place to start and make real progress toward even the biggest goal. Once you’ve settled on a long-term goal, write it at the top of the whiteboard. It’ll stay there throughout the sprint as a beacon to keep everyone moving in the same direction.” (Jake Knapp, Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days)

How do you decide on a long-term goal?

You ask the team a simple question, says Jake Knapp: “Why are we doing this project? Where do we want to be six months, a year, or even five years from now?” (Sprint)

Again, the Decider will be the one choosing the target (the type of customer or market) and long-term goal.

Figuring out the Sprint Questions

Now that we know the long-term goal, we’re all optimistic that we’ll succeed.

To balance that rosy outlook, we need the sprint questions. These will question the underlying assumptions beneath our goal. The sprint provides a perfect setting to examine assumptions and get answers to our questions about them.

“An important part of this exercise is rephrasing assumptions and obstacles into questions,” writes Jake Knapp in Sprint. “[…] Turning these potential problems into questions makes them easier to track—and easier to answer with sketches, prototypes, and tests. It also creates a subtle shift from uncertainty (which is uncomfortable) to curiosity (which is exciting).”

“You have to ask your team what questions they need to answer to move on solid grounds, to get to your long-term goal,” adds Jeff Mignon.

Questions to face your fears

How many questions should you have? It doesn’t matter, says Jake Knapp:

“You might end up with only one or two sprint questions. That’s fine. You might come up with a dozen or more. Also, just fine. If you do end up with a long list, don’t worry about deciding which questions are most important. You’ll do that at the end of the day on Monday when you pick a target for the sprint. By starting at the end with these questions, you’ll face your fears. Big questions and unknowns can be discomforting, but you’ll feel relieved to see them all listed in one place. You’ll know where you’re headed and what you’re up against.” (Sprint)

What does a sprint question look like?

Here’s an example from the book Sprint:

“It’s not difficult to find an assumption such as Blue Bottle’s and turn it into a question:

Q: To reach new customers, what has to be true?

A: They have to trust our expertise.

Q: How can we phrase that as a question?

A: Will customers trust our expertise?”

As you see, rephrasing a problem into a question is not difficult.

Here’s another example about a fictional laundry service, this time from A.J. Smart:

Obstacle: “People won’t need a service like this because they already own a washing machine.”

Question: “Can we replace the need for a washing machine?”

“Can we…”

This last question used the format: “Can we… do something?”

Coming up with “Can we” questions is the way we deal with pessimistic issues that may arise.

“Each participant creates pessimistic questions, explains Jeff Mignon. That’s our way of doing a brainstorm together alone. It’s part of the process of creating the right sprint questions.”

After this individual brainstorm, each participant presents his or her “Can we” questions.

Then, everyone gets to dots to vote, except for the Decider.

Equipped with the opinions of everyone, expressed by the dots, the Decider than chooses the top “Can we’ questions. And from these, he or she creates sprint questions.

Now, it is time for lunch already?

Nope. We still must create a map.

Mapping the problem

“The map is a big deal throughout the week. […] You’ll use the map to narrow your broad challenge into a specific target for the sprint. Later in the week, the map will provide structure for your solution sketches and prototype. It helps you keep track of how everything fits together, and it eases the burden on each person’s short-term memory.” (Jake Knapp, Sprint)

So, what is this map?

It is a simple diagram, essentially customer-centric, that shows your customer’s journey through your product or service.

It tells the story of each step the customer has to take to end up buying your product or using your service.

“The map should stay very simple, says Pentalog’s Jeff Mignon. The whole idea is to illustrate a complex situation as simply as possible.”

The map should show:

- The actors of the story

- The ending

- Words, boxes, and arrows to show the steps (no more than 20 to keep it simple)

Start with the end in mind, said some business thinker (Covey). That applies to the Design Sprint Workshop too. And to the drawing of the map.

By knowing the end, it’s easier to map the middle.

While drawing your map by yourself, you should consult the rest of the team, recommends Jake Knapp, to find out if you’re on the right track.

Now, it’s time for lunch

OK, now it’s time for a light snack to stay sharp in the afternoon.

While you eat, think about what you have already achieved: you have picked a long-term goal, you know which sprint questions you’ll work with, and you have a map.

Congratulations. See you in a bit.

In the meantime, if you want to discuss your challenges, talk to us.

The Design Sprint Workshop series:

The Design Sprint Workshop: Defining the Challenge (Part 1)

The Design Sprint Workshop: Creating Solutions (Part 2)

The Design Sprint Workshop: Voting Day (Part 3)

The Design Sprint Workshop: The Storyboard (Part 4)

The Design Sprint Workshop: Prototyping (Part 5)

The Design Sprint Workshop: Testing (Part 6)